12 Min Read

June 27, 2025

By

Sara Castelo Branco is a curator and writer based in Portugal. Her work bridges media cultures, postdigitalism, political ecology, and social resilience. She holds a PhD in Arts and Sciences of Art (Paris 1/UNL) and teaches at Universidade Católica Portuguesa. She has curated exhibitions and screenings across Europe and writes regularly for publications including Mousse, Contemporânea, and Archive Books.

The philosopher Michel Serres (1980) once defined the sun as our energetic horizon and the “ultimate capital” in the history of modern religion, culture, ecology, and economy. One of the foundations of solar capital is its relationship with energy, which has long shaped ideologies related to work, progress, imperialism, and productivism. In this sense, solar energy constitutes one of the most important themes in the current context of international politics given its geopolitical importance: the circulation of power between those who control energy production and those who depend on it.

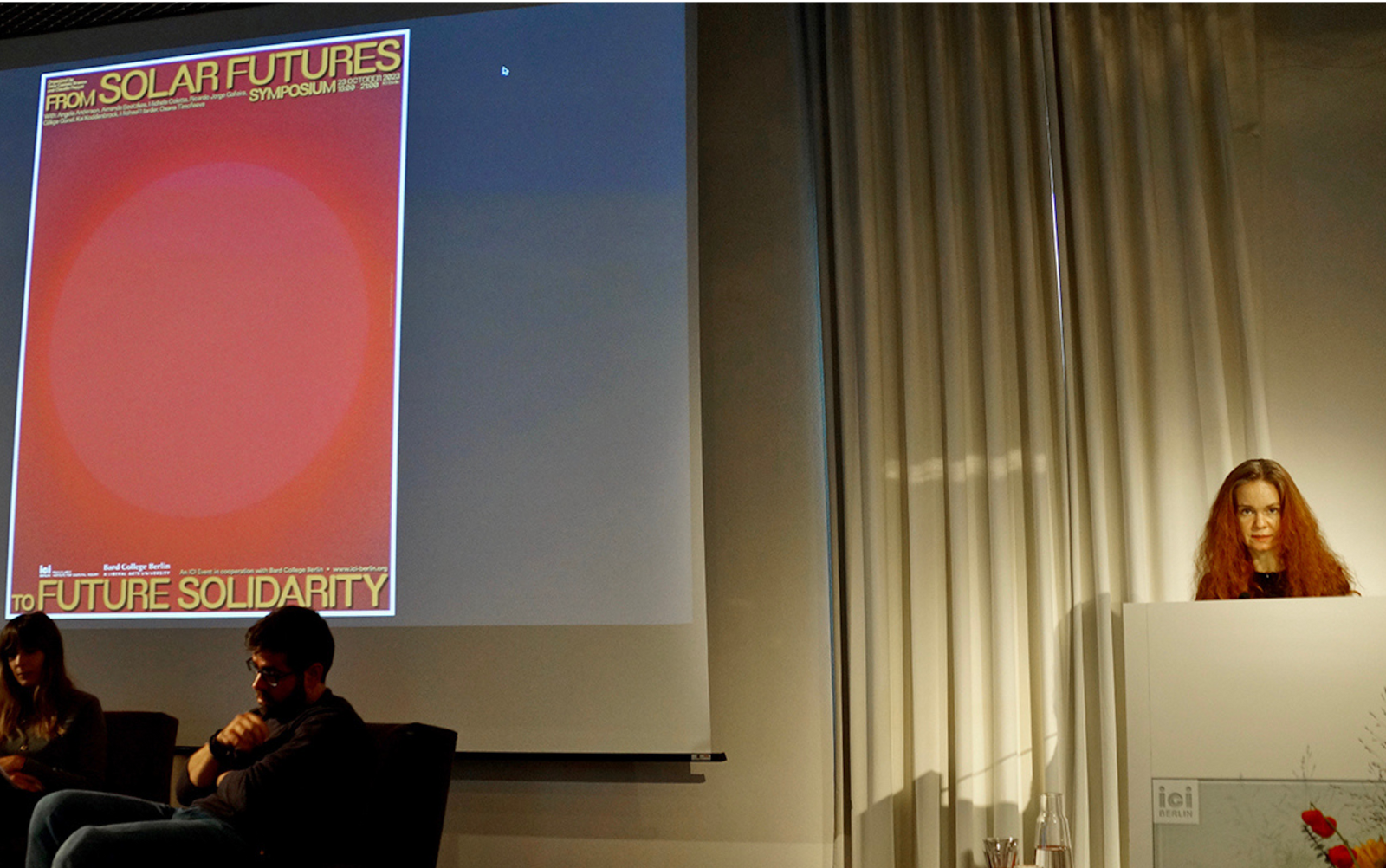

In an effort to explore how futures of solarity and solidarity can be both sustainable and equitable, Sara Castelo Branco and Claudia Peppel organized the From Solar Futures to Future Solidarity symposium in October 2023 at the ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry, in cooperation with Bard College Berlin.1 The symposium was part of a broader project named Solarity Prospects, which sought to think about solar energy as a possible mechanism of contestation against forms of neoliberalism, autocratic systems, and the climate crisis.2

The symposium’s first presentation was “The Roles of the Sun Over the Last Centuries” by solar physicist Ricardo Jorge Gafeira, who discussed the various roles of the sun in society, from its deification in the past to its current scientific understanding in a technologically dependent society. Gafeira focused in particular on the sun’s cyclical transformations known as solar cycles that last approximately 11 years. These cycles manifest as fluctuations in sunspot numbers that are correlated to the existence of solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), variations in solar radiation, and many other observed structures and indexes. These cycles can affect space weather and consequently disrupt the Earth’s magnetic field, communication systems, and many other electronic systems, leading scientists and agencies to monitor and predict space weather to mitigate this impact, which somehow evidences our technological fragility in the face of solar phenomena.

Considering another possibly damaging element associated with the sun, philosopher Oxana Timofeeva’s presentation, “It Is Never Too Early to Decolonize Sun,” explored literary examples of different ways of overcoming or even colonizing the sun. Timofeeva’s examples included Aleksei Kruchonykh’s futurist opera Victory Over the Sun (1913), in which the sun represented a romantic nature threatened by progressive technologies and abstract forms; Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s science fiction novel Dreams of the Earth and Sky (1895), which alluded to humanity’s eventual colonization of the Milky Way galaxy; and Olaf Stapledon’s novel Star Maker (1937), in which the elimination of the sun was imagined to meet humanity’s economic needs for many ages to come. For Timofeeva, this speculative colonization testified to the structural relevance of this term when considering the components of the solar system as disposable goods: “the sun can be taken as an image of the other in whom we would never recognize ourselves (like the slaves), but at the same time, that would serve as this idea of a paradoxical solidarity.” According to Timofeeva, although solar energy promises a democratic and decentralized individual use, it is still oriented towards harmful relationships and inequalities even in the most sustainable economic projects, running the risk of remaining trapped within the evil infinity of colonial extraction.

Focusing his analysis on the relations between Europe and Africa, political economist Kai Koddenbrock presented “German Africa Policy: From Eurafrican Utopias to Another Scramble for African Resources?,” a discussion of Euro-African utopias that animated the European gaze during the early 20th century, relating them to the contemporary remodelling of German approaches to African “partners”. Koddenbrock argued that there is a long tradition of European “valorization” of the African continent, and green hydrogen (and the solar energy required for it) has intensified a “new rush for Africa”. In light of this history, he proposes a future German progressive policy based in three principles: the recognition of the climate crisis, colonialism and slavery; the support for the mobilization of internal fundraising; and, the promotion of regional complementarities.

Incorporating other geo-economic perspectives, Gökçe Günel in the presentation “Leapfrogging to Solar” looked at how the creation of solar power plants has been an integral part of China’s broader influence in Ghana, as Chinese companies have financed and facilitated the construction of these infrastructure projects, often in exchange for access to raw materials. One example is the relationship between two of the largest solar power stations in West Africa (owned by Chinese technology company Beijing Fuxing Xiaocheng Electronic) and sugarcane plantations: the Bui Power Authority has leased 13,000 acres of land to Bui Sugar Limited, another Chinese company. These facilities are governed by a framework of expropriation that depends on the region’s cheap land and readily available workers. In this sense, Günel concludes that the solar energy future is attractive because it allows for grid expansion, that many energy professionals consider to be in an ethical way, but this is “a utopian goal that now manifests itself in the form of corporate enterprises of different sizes and shapes such national and planetary scale cleaning depended on the thankless task of wiping solar panels each and every day.”

In “Queer Eco-intersectional Luxury Communist Solarities Against Capitalist Authoritarianism,” artist and researcher Angela Anderson addressed the socio-energetic context of Florida, the so-called Sunshine State, where the production of solar energy, the right to abortion, queer and trans rights, anti-racism, and social justice have become inextricably intertwined in different ways. Florida averages 230 days of sunshine per year, but despite sunlight being one of the state’s most abundant and free resources, Florida Power and Light produces more than two-thirds of its electricity from natural gas, followed by nuclear, which represents almost 20%. According to Anderson, the current city government secured “the future of fossil fuel pro produce electricity in the state, signing legislation, which prevents cities from passing ordinances, which would ban the use of a particular energy fuel source, essentially protecting FPLs natural gas investments.” Given this context, Anderson suggests that this continual descent into an abyss can be thwarted through a platform of queer anti-racist feminist vision for a solar future with “transparent democratic structures open and on-going discussions about social justice and reparations, academic freedom, drag shows, unrestricted access to free abortion, renewable and affordable energy rainbows, and of course sunshine”.

In “Capitalist Prize-Fighter: Solarity’s Observers of Modern Life,” Amanda Boetzkes questioned who today’s fighters are and what their sacrifice tells us about solarity. In line with the surrealist interest in bullfighting, she considered some examples of contemporary boxing matches, and what they tell us about modes of capital exchange and their dependence on a spectacle of life and death. The presentation focused particularly on Georges Bataille’s writings about a bullfight (lit by an excessive sun) in the book The Story of the Eye (1928), where he addresses the idea that the sun gives us the desire to live and be free, but at the same time it attacks us. Given this context, Boetzkes states that not only do we consume as we see, but we are also consumed by our own vision. It thus becomes clear that visibility itself is the prize-fighter in a solar exchange.

On the other hand, philosopher Michael Marder reflected in On Heraclitus, Fr. 6: ‘The sun is new every day’ on the meaning of one of the ‘fragments of the sun’ attributed to the pre-Socratic Heraclitus, considering it in a relationship with the perennial theme of rebirth, divinity, newness, the immeasurable or the transgression of limits. Despite the miscellany of sources classified as renewable energy, this conceptual paradigm strives to “make of the notion that the sun is new every day a practical principle, a potentiality (renewability), and a power that could be projected into the future, indefinitely.” As part of this reading, Marder considered the Portuguese government’s plans to install three gigantic solar power plants in Santiago do Cacém. If the plan comes to fruition, this “mega solar park” (the largest in Europe) would occupy 6% of the municipality’s land and would require the felling of a/1 million trees: “the earth covered by solar energy panels versus 1.5 million suns that are new every day in the arboreal existences that elaborate it, lending it an extended body in articulation with the decaying organic matter of the soil.”

Considering an analysis equally related to the dangers of replicating a managerial-extractivist model, “Being Planetary: From Managerial Cartography to Post-anthropocentric Solidarity” by Michela Coletta evoked the potential of a non-anthropocentric planetary solidarity, a process in which humans are neither saviours nor ecological agents, but constitute eco-social communities in which energy can be the main currency by “contrasting the logic of the totality of an energy extraction planetary with the wholeness in its Latin etymology of solidus – whole of a, an eco-social solidarity.”

Given this idea of solidarity as what is common, this symposium reflected on the complexities of solar energy in several dimensions to dispute forms of heliocentrism that develop procedures of marginality, appropriation, and energy imperialism. The idea of prospects deviated here from its utilitarian meaning to favour its temporalized sense (from the Latin prospicere ‘look forward’), being associated with the unity of feeling and action of solidarity: to encourage the idea that it is essential to seek solar futures and future solidarity which pursue answers that promote a future with regard to energy production.