12 Min Read

August 28, 2025

By

Harry Pitt Scott is a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow in the English Literature Department, University of Glasgow, and a member of the Infrastructure Humanities Group. His research interests include the social dimensions of infrastructure change and the political cultures of energy transition, with particular interest in the politics of renewables. His current research project is on electrification, techno-utopianism, and science fiction.

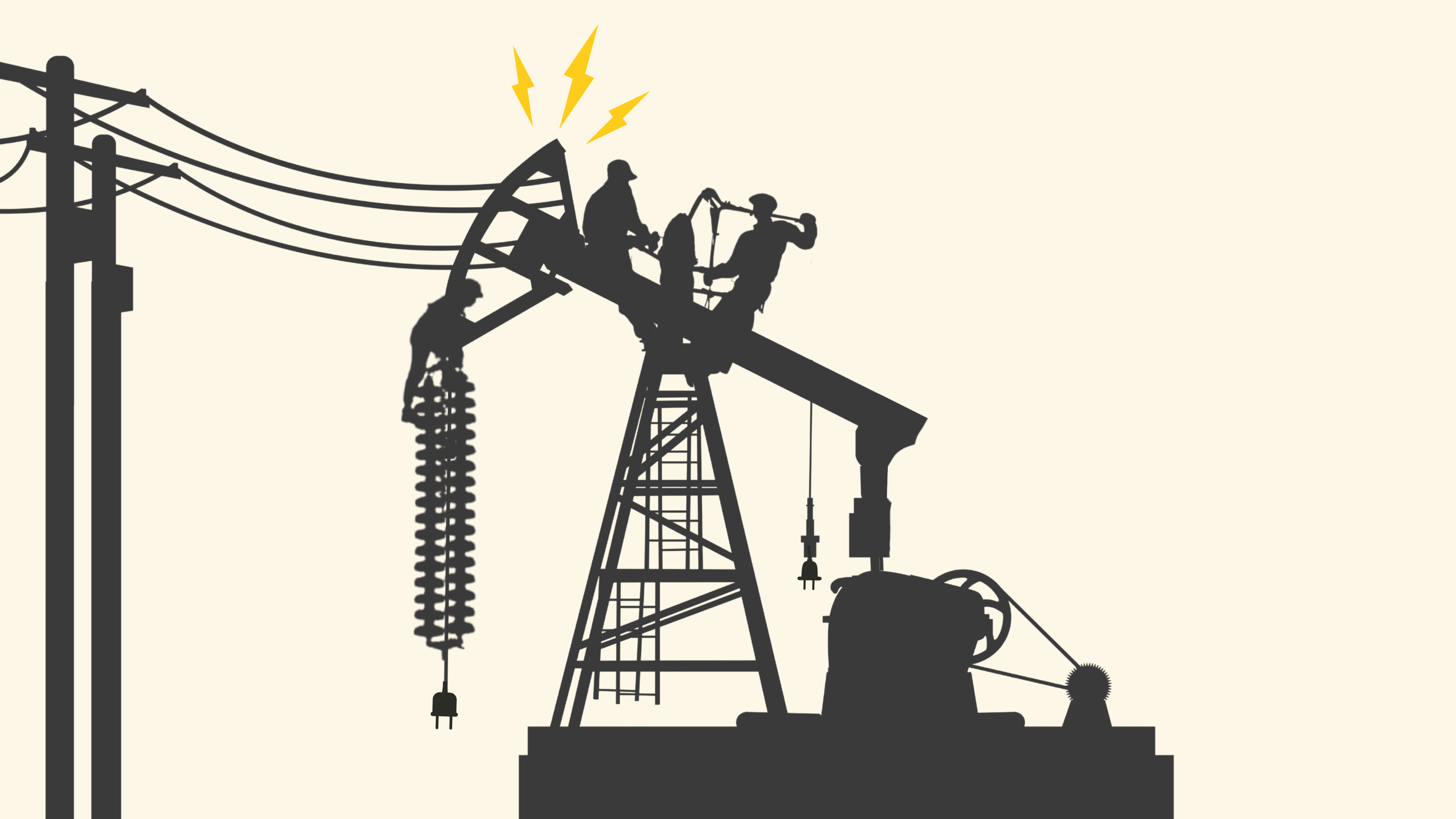

The promise of electrification—the replacement of carbon-emitting technologies with electric-power equivalents—has begun to operate as the organizing grand narrative of the energy transition. “Electrify everything” is the new guiding mantra for the shift away from fossil fuels, shaping climate policy, technological innovation, and investment strategies. Electrification has increasingly come to define energy and climate futures, with the IEA describing electricity as the “new oil,” given its importance in ushering in a green transition.1

Electrification is central to the IEA’s transition scenarios. Because most electricity is generated by coal- and natural gas-fired power stations, it is currently the largest contributor of carbon emissions worldwide. Decarbonizing the sector through the expansion of renewable and nuclear power sources is essential. Alongside this growth in clean electricity supply is the expansion of end-use electrification as electricity replaces fossil fuels to provide heat, mobility, and industrial energy for hard-to-abate sectors like steel and ammonia. Heat pumps, electric vehicles, and hydrogen production all contribute to major projected rises in electricity demand in the years to come.2

Despite such projections, growth in clean power generation has not kept pace with global electricity demand. Global electricity generation has nearly doubled the growth in low-emission electricity sources (8400 TWh to 4800 TWh). Coal and natural gas have filled the gap. Even in STEPS (the Stated Policies Scenario), the IEA’s most conservative scenario, global electricity demand nearly doubles by 2050. In its most optimistic (the Net Zero scenario), the equivalent of over fifty percent of today’s electricity demand is used to produce electricity for industrial energy alone, more than global clean electricity generation in 2025.3 If every existing wind farm, solar panel, nuclear power station, and hydroelectric dam were put to this purpose overnight, they would fall short by about 4,000 TWh, roughly equivalent to the United States’s electricity consumption in 2023. This is to say nothing of the expansion in storage batteries required for a stable grid powered in large part by renewables, the need for carbon capture and storage, and large-scale hydrogen production. There is a considerable gap between where we are and the IEA’s future of everything electrified.

Yet for all the techno-speculation needed to achieve full electrification, the result is often now treated as a given. The work of green entrepreneur Saul Griffith exemplifies this kind of thinking. For instance, his book Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for our Clean Energy Future (2021), claims that full electrification is not only possible with current technology but will provide such significant efficiency improvements that global energy needs will be halved in the process. As important as this technological claim is the social vision it is attached to. He writes that

Winning the war against the climate crisis will also mean a cleaner, more positive future. Our houses will be more comfortable when we shift to heat pumps and radiant heating systems that can also store energy. While it may also be desirable to downsize our homes and cars, this isn’t absolutely necessary, at least in the US. Our cars can be sportier when they are electric. Household air quality will improve, as will public health, since gas stoves raise the risk of asthma and respiratory illnesses. We don’t need to switch to mass rail and public transit, nor mandate changing the settings on consumers’ thermostats, nor ask all red meat–loving Americans to turn vegetarian. No one has to wear a Jimmy Carter sweater (but if you like cardigans, by all means wear one)! And if we sensibly employ biofuels, we don’t have to ban flying. In short, the climate-friendly future will be quite recognizable in terms of the major objects in our lives—our cars, homes, offices, furnaces, and refrigerators. All of these objects will just be electric.4

The promise of electrification, in other words, is that next to nothing needs to change at all in our petrocultures.

Perhaps it is unsurprising that such a familiar discourse is resurfacing at a time of climate crisis. To imagine electrification as a solution to the social contradictions of carbon modernity is a time-worn tradition.5 But what is most striking about the predictions of the IEA, Griffith, and others is how they simultaneously promise so much and so little. Carbon modernity is to be entirely remade, but the form in which the future is cast is entirely recognizable. This narrative has none of the dynamism and excitement that accompanied the electrification of America in the nineteenth century, which, as David Nye relates, brought with it the promise of a “harmonious community, a world apparently without inequality.”6 This electro-utopianism is best captured by utopian writer Edward Bellamy, who described a world in which electricity has “taken the place of all fires”: gone are the industrial cities mired in gloom, the class war between bourgeois and proletarian, and the ruination of the country.7 Electricity infrastructure was invested with a telos, a narrative of progress, and a promise of social and ecological harmony—in short, the redemption of carbon modernity. The resignification of electricity from a symbol of a utopian future to the persistence of the ongoing now of petroculture makes Griffith’s entrepreneurial promise of electrification different from earlier electric futures. Griffith’s rhetorical style suggests a clear-headed engagement with the reality of an immutable political and social configuration, bracketing and dismissing any suggestion that electrification might offer the possibility of change.

Instead, for Griffith, the problem is the by-product of carbon-emitting technology, not the technology itself. Electrification makes imaginable a “clean” version of petroculture while leaving intact its social relations. Griffith describes his transition program as the application of familiar financial instruments such as car loans and mortgages to privately-owned renewable infrastructure like EVs, solar panels, and heat pumps—all integrated into smart grids, an infrastructure described as a natural, inevitable progression on the inefficient, wasteful, and bureaucratic centralized grid. With the requisite funding and market conditions, the transition can bypass the political entirely, if only all electricity consumers (or “prosumers”) can be transformed into market actors.8 A rhetoric of the new has been replaced with a rhetoric in which new technologies simply substitute for the old, leaving the world around them the way it is.

If Griffith imagines electrification to displace political reasoning, the rhetorical form that this promise takes is the association of electricity with a clean and positive future. Despite this familiar ethos, electrification has never really been clean in an ecological sense because it leads to increased demand for coal-fired plants, nor has it delivered the oft-promised social harmony. The separation of carbon-emitting thermal generation from odourless and smokeless light, heat, and power—or, in the case of EVs, fossil fuels from engine power—enables a conceptual coupling of cleanliness and electricity. The “lingua franca of energy forms,” according to Griffith, electricity bears no trace of its origins, carbon or otherwise. This also gives it substantial explanatory force, always able to stand in for or replace other energy forms, if only for now in the imagination.

Even decarbonized electricity has a high material throughput. Thermal generation and steel production are necessary to build electricity infrastructure, and these will consume vast amounts of fossil fuels unless they can be replaced by electric-powered “green steel.” The new economic geography of the green transition—often where the most brutal aspects of capitalism are playing out—involves extracting rare earth metals using technologies powered by coal and gasoline and transported by gasoline-guzzling infrastructures. These too must be substituted for green equivalents. Electrification is pitched as a recursive and flexible solution, simultaneously possible and necessary at every step and scale of transition. If this rhetoric pushed by contemporary futurologists evokes a clean harmonious future just over the horizon, electrification at present remains a carbon intensive endeavour.

Electrification may be our best hope for mitigating the worst of the climate crisis. But we must be wary of the way the promise of everything electrified reinvigorates the ideological and moral claim of entrepreneurs and investors to guide us through the energy transition. Griffith exemplifies a discourse grand in technological promise and modest in social reform. He offers clean substitution as the progressive force of modernity, the present in the future’s clothing. This narrative is appealing because it introduces a solution to political deadlock and infrastructural inertia: by removing from electrification all association with transformative social change, it narrates the shape of transition as a fait accompli. In this future, public ownership, robust democratic debate, and cultural change have no role to play in the electrified world to come, because these will only get in the way of bringing it about.

If electrification is to be the primary driver of the energy transition, we should articulate a vision of electrification that breaks with the fantasy that, if we surrender to the dictates of markets and entrepreneurs, technological progress from fossil energy to clean electricity is inevitable. That might require alternative models of ownership to that of the private loan and the mortgage, and alternative forms of subjectivity to the market-savvy prosumer. These are, after all, capitalism’s electric dreams—but they need not be ours.

Notes

1. International Energy Agency (IEA), World Energy Outlook 2022, October 27, 2022, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022, 72.

2. International Energy Agency (IEA), World Energy Outlook 2024, October 16, 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024, 45-50.

3. Ibid., 43-45.

4. Saul Griffith, Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for Our Clean Energy Future (MIT Press, 2021).

5. James W. Carey and John J. Quirk, “The Mythos of the Electronic Revolution,” The American Scholar 39, no. 2 (1970): 219–41.

6. David Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880–1940 (MIT Press, 1992), 371.

7. Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward 2000–1887, ed. by Matthew Beaumont (Oxford University Press, 2009).

8. Canay Özden-Schilling, “Economy Electric,” Cultural Anthropology 30, no. 4 (2015): 578–88, https://doi.org/10.14506/ca30.4.06.