12 Min Read

November 12, 2025

By

Nate Otjen is assistant professor of sustainability and environmental studies at Ramapo College where he studies and teaches multispecies justice and renewable energy development. He holds a PhD in Environmental Sciences, Studies and Policy from the University of Oregon. From 2022-24, he was a Postdoctoral Fellow in the High Meadows Environmental Institute at Princeton University. He co-leads the Mining for the Climate podcast produced by Blue Lab.

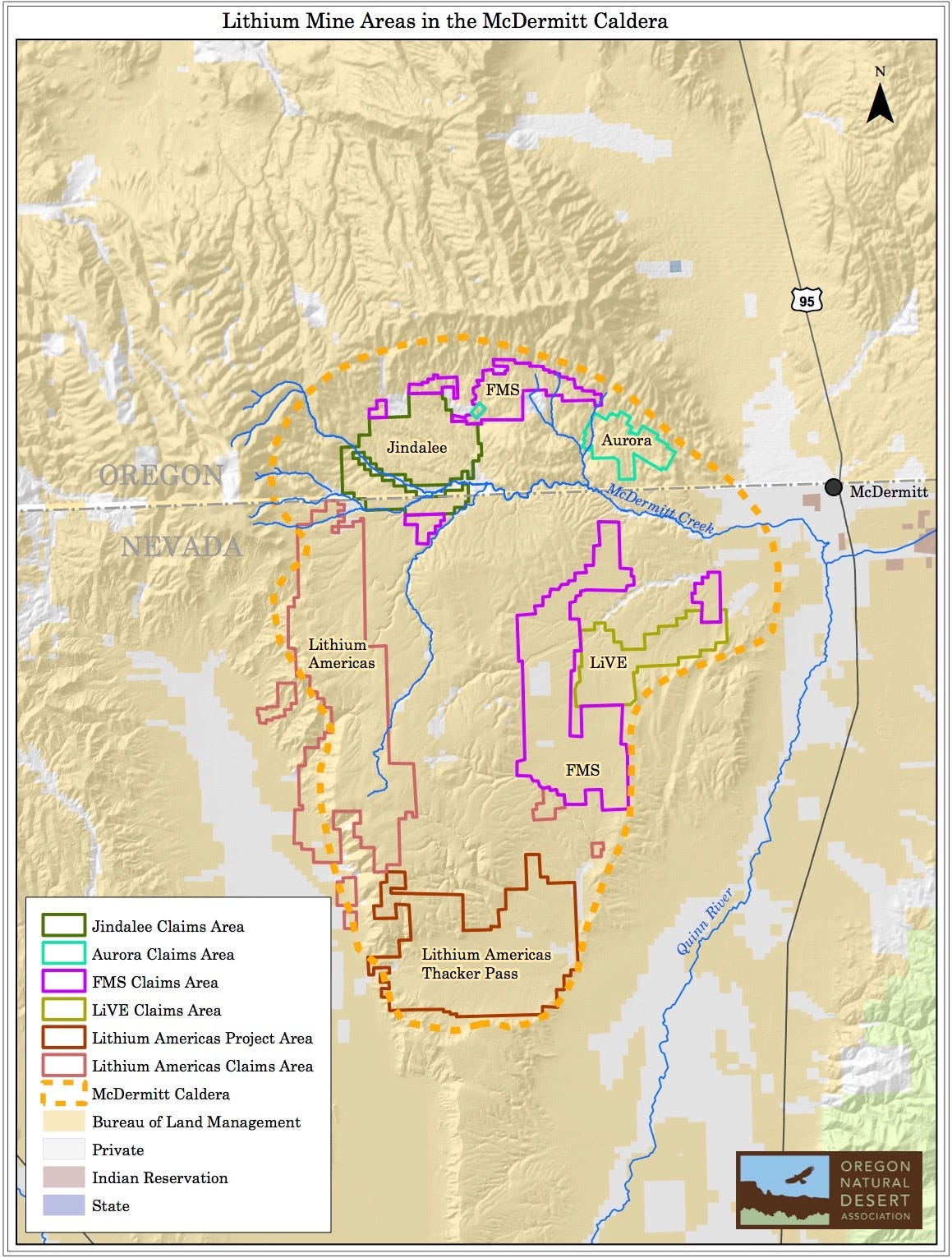

A monumental energy development project is underway in the high desert of northern Nevada and southern Oregon. Lithium Nevada, a subsidiary of the mining corporation Lithium Americas, is scraping away sagebrush to build a sulfuric acid plant, processing facility, and open pit mine. Backed by a $2.26 billion loan from the US Department of Energy, this taxpayer-funded project will permanently alter thousands of acres and impact millennia-long relations. At the same time, at least four other mining companies have purchased mineral claims throughout the caldera, including Jindalee Lithium, FMS Lithium Corporation, Aurora Lithium, and Arcadium Lithium (formerly Livent Corporation). [Figure 1] Despite substantial opposition from residents and national and international allies, these five companies — with support from the federal and state government — are redefining this place and, in the process, rewriting its future.

Contrary to settler views of arid land as empty, the McDermitt Caldera teems with life. Once a large volcano that, over millions of years, collapsed inward, became a lake, and then emptied, its unique geologic history has made it rich in both life and lithium. The Lahontan cutthroat trout which once swam in the crater’s lake now traverses the numerous spring-fed streams that cut through the landscape. The streams give rise to dense stands of aspens and colorful meadows that are home to species ranging from red-winged blackbirds to cattle and spring snails. The rolling hills of sage brush host animals like western sage grouse, golden eagles, sage brush sparrows, jackrabbits, and pronghorn antelopes, many of which are threatened or endangered. Paiute and Shoshone peoples have been living with this land for millennia and have long fought to maintain access to it. More recent arrivals, such as ranchers and recreationists, also find meaning in this place. [Figure 2]

The caldera has been publicly accessible since Nevada became a state in 1864. Anyone could visit to hunt, fish, gather, hike, or conduct research. When lithium became an economically viable mineral commodity in the late 2010s, however, access began to change and so did views toward the land. To many, the McDermitt Caldera now represents a valuable and necessary mineral resource, one that will unlock US battery independence, boost the economy, and strengthen national security. The caldera is no longer public land brimming with ecological and cultural importance. Instead, it is rapidly becoming an energy colony, a site of industrial-scale extraction controlled by business interests.

The term “energy colony” evokes a number of images and feelings. For those of us living in the affluent north, it may call to mind an oil field covered in derricks, or perhaps the tar sands in northern Canada. For others, it brings to mind the violent history of colonial trade and Native dispossession. And for others still, it triggers thoughts of a sci-fi colony on a distant planet. The term is compelling, in part, because it raises so many associations.

Without imposing a monolithic definition, I suggest that there are several core features of the twenty-first-century energy colony that make the concept productive to think with. First, energy colonies operate at massive scales. The primary goal is to extract an energy resource and make a profit. Due to this, they often require transformations that extend to the wider region, including infrastructure and supply chain development. Second, energy colonies operate within multiple temporalities. Companies often describe lithium mining, for instance, as a “frontier” of energy development, drawing upon genres like science fiction to describe new technologies and their possibilities. In reality, however, the mining practices deployed in the McDermitt Caldera have been borrowed from the coal industry. Far from breaking with the past, lithium mining participates in longstanding colonial histories, including land dispossession and industrial development and pollution. Finally, energy colonies show how colonialist and capitalist logics intersect to transform places, often in ways that are negative for local communities and nonhumans. Studying them exposes the collusions between business and government, along with the injustices that follow from extraction and overconsumption.

In the second season of the audio documentary series Mining for the Climate, I set out to understand how the McDermitt Caldera is becoming an energy colony and how residents are opposing lithium development. (The first season takes listeners to a proposed lithium mine in Gaston County, North Carolina, and examines how different narratives produce particular paths for the energy transition.) Told from my perspective and the viewpoints of my collaborators at Princeton University, the four episodes in Season 2 chart the emergence of the McDermitt Caldera energy colony.

Since completing interviews in late 2024 and releasing the second season in May 2025, however, several major developments have occurred. By way of bringing Energy Humanities readers up to date and introducing some of the major themes in Mining for the Climate, I offer three observations that may help energy scholars make sense of the growing energy colony in the McDermitt Caldera.

Infrastructure

Lithium mines need robust infrastructures in order to operate. Materials and people must be transported to and from worksites, which requires extensive roadways, rail systems, and energy networks. In “remote” areas like the McDermitt Caldera, which has only two major north-south highways (Route 95 to the east and Route 140 to the west), companies must build, or convince state and local governments to build, new roads. To construct the Thacker Pass Mine, Lithium Nevada is in the process of altering State Route 29,3 which runs past the mine, along with building new rail lines and housing centers.

New infrastructure projects also enable the tightening of control and the concentration of power. Building water systems and purchasing energy rights can make rural, impoverished places like Humboldt County, Nevada, indebted to mines while, at the same time, it can give mining companies greater regional control and influence. Moreover, once it is built, it becomes harder to fight mining activities or close existing mines, as expensive infrastructure can be used to justify ongoing operations. Infrastructure projects are typically the second-most contentious part of any lithium project. In many cases, taxpayers are asked to fund upgrades and changes, often with the vague promise that doing so will bring economic prosperity to the region later. Infrastructure allows energy colonies to operate and exert control, and it paves the way for their expansion.

Expansion

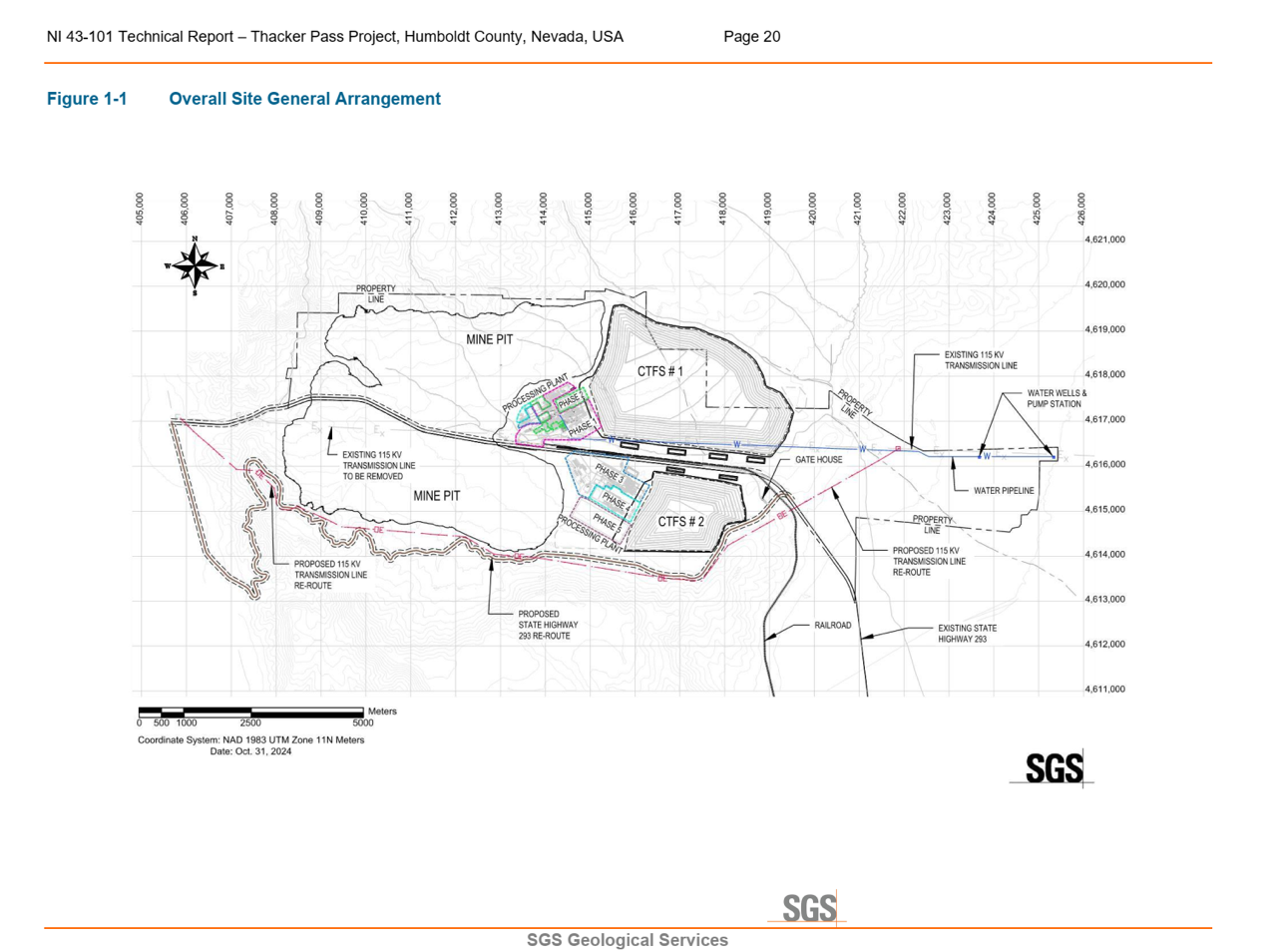

Final approval of a lithium mine sets into motion a flurry of activities. One of the first actions many companies take involves expanding the footprint and size of the mine, often without telling communities. In December 2024, to the surprise of residents, Lithium Nevada announced the addition of three new “phases” which would effectively double the size of the Thacker Pass Mine. The plans also included dramatic infrastructure changes, including closing off part of State Route 293 and building an alternate route further south, along with moving a major electricity transmission line that currently bisects the site. [Figure 3]

Government approval of the mine also encourages other companies to pursue their own projects in the region. In April 2025, Australian-owned Jindalee Lithium advanced a proposal to develop an exploration project on the Oregon side of the McDermitt Caldera. Their plan calls for developing up to 261 drill sites, building up to 30.2 miles of roads, and constructing up to 40 groundwater monitoring wells over a 7,200-acre area. The company will use the findings to develop plans for a mine and processing facilities.

These developments cannot be separated from the political climate, one that is increasingly supportive of critical mineral projects. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have supported fast-tracked federal permitting for critical mineral mines on public land. In May 2025, the Supreme Court moved Rio Tinto and BHP a step closer to developing the Resolution Copper Mine in Oak Flat, Arizona, a place sacred to the Apache people. Two months prior, the Trump Administration placed Resolution Copper on a list of nine other critical mineral projects approved for fast-tracked permitting. At the same time, digital platforms like Heatmap Pro promise to identify places in the US where mining can proceed with less resistance. One of Heatmap Pro’s mapping tools even seeks to “quantify political risk facing planned or operating projects.” Mining, in other words, begets more mining.

Access and Surveillance

As I noted earlier, energy colonies seek to concentrate control and power. In the McDermitt Caldera, this has meant restricting access to land that was previously accessible and partnering with the state to monitor the activities of those it deems a threat. ProPublica released a story in July 2025 detailing how the FBI and other law enforcement agencies collaborated with private security firms to monitor peaceful protesters who opposed the construction of the Thacker Pass Mine. Many of these protestors are Paiute and Shoshone. Unbeknownst to them, federal and state law enforcement agencies monitored their social media pages, and, in one instance, video recorded their activities. Lithium Nevada even hired a former FBI agent who specialized in counterterrorism to create the security plan for the mine.

The presence of security officers near the Thacker Pass Mine has been a central issue for community members, especially Paiutes and Shoshones seeking to access their ancestral lands. For nearly five years now, white security trucks have been driving up and down State Route 293, stopping to question people if they see them pull off the road to take photos or use the public access roads to enter or leave the caldera. As Day Hinkey, a member of the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe, puts it in the second season of Mining for the Climate, “It’s a tactic to say ‘Hey, stay out of here’.”

Surveillance is a form of control. For Lithium Nevada, control means not only limiting access to the physical area but also managing the dominant narrative about the mine, especially the narrative that the mine is necessary and good. Should the McDermitt Caldera become a full-fledged energy colony, its entire perimeter could be placed under surveillance.

Gary McKinney, an enrolled member of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation and one of the protestors tracked by the FBI, coined the phrase “Life over lithium” to describe an oppositional view of the McDermitt Caldera, one that challenges the vision of the energy colony and ascribes greater value to the region’s diverse life forms. [Figure 4] The phrase, which has been displayed on billboards throughout the region by the Native-led group People of Red Mountain, also implies that life and lithium cannot coexist. As Gary explains, “What’s going on today in the green energy transition, the corporations, the jobs, the money — it’s all missing spirit. It’s all missing the human spirit. It’s operating without that. And we need that. It’s essential to us.”

Keeping lithium in the ground would mean rejecting the energy colony and, in its place, preserving the life that Gary and the people of this place know so well.

You can listen to Mining for the Climate wherever you stream podcasts.

Many thanks to Blue Lab at Princeton University, especially Allison Carruth and Barron Bixler, along with last year’s Mining for the Climate research and storytelling team: Jessica Ng, Christopher Bao, and Jose Santacruz. Thanks also to Susan Frey, Edward Bartell, Kyle Keeler, and Christopher Bao for calling my attention to recent news stories. Finally, I thank Imre Szeman for the invitation to contribute to Energy Humanities.