12 Min Read

November 3, 2025

By

Lisa Moore, author of February, Caught, and Alligator, teaches creative writing at Memorial University. She has edited multiple anthologies and co-authored the opera February. Sheena Wilson, Professor at the University of Alberta, co-founded the Petrocultures Research Group and leads Just Powers. Her feminist, decolonial research examines extractivism’s social and environmental impacts. Their edited volume We Were In It: Stories About Energy Transition is available at Memorial University Press.

We were interested in how petrocultures touch down in the most intimate parts of our lives: our relations with others; our deepest loves; the violence in our symbiotic untangling relationship with nature and the ruined and forever fouled; the experience of loss and being lost.

Fiction can get at these often inchoate, intimate, secret, deeply buried, coal-hardened, glittery hearts of who we are, the parts we need to free with a pick or a mallet, or the parts of us that flick past like wisps of smoke or exhaust.

Fiction can also get at the question of agency: how we act upon the world to change it; and how the world acts upon us.

So, we wrote fiction. As a group, we had varying degrees of experience with writing fiction, so we started small. We would write complete but bite-sized stories, flash fiction. The word flash is apt, the emission of energy transforming darkness to light, however briefly; an understanding or insight or epiphany that comes without obvious mental labour – it simply occurs. From nothing, something. Form, meaning. A flash. Flashes.

It seemed to us, as editors, that this approach to thinking about energy transition would help the authors in the collection glean new insights, though it’s not the way either of us normally write fiction. Lisa typically begins with characters who are undergoing some kind of crisis. She believes if her characters are accurately drawn, if they provoke suspension of disbelief and if they live and breathe on the page, the wider social and political implications of what she writes will accrue. But as an experiment, she was willing to start from the other end, with the social and political characteristics of petrocultures, to see what kind of characters would emerge. Sheena thinks about petroculture as a character: a multi-headed, tentacular, polymeric Hydra that oozes into the interstices or swallows us whole but leaves none of us untouched. Who have we become in relationship to her? A paradox: do we shape society while society is shaping us? And then there’s the question of who ‘us’ is; of who can speak and the unequal power dynamics that are altering our climates in different locations all over the world. Strong fiction has always contained the universal in the particular, and vice versa, or strives to do so, however it may fail.

Offering lectures on various elements of the craft of writing and focusing on the building blocks of fiction – character; plot; setting; genre (particularly the supernatural); voice; imagery; etc., along with a specific prompt about energy transition, such as: write about a time when you experienced a loss of power – these were the controlled methods of our experiment.

We called this experiment research-creation, believing that there is no creation without research, and no research without creativity. But art is unruly and petulant and parts ways pretty quickly with controlled methods.

Fiction can get at these often inchoate, intimate, secret, deeply buried, coal-hardened, glittery hearts of who we are, the parts we need to free with a pick or a mallet, or the parts of us that flick past like wisps of smoke or exhaust.

People wrote during workshops over Zoom and each story had to come together in a heartbeat. The writers were capturing the synaptic leaps of thoughts and feelings without time to reshape or edit or cut away the terrifying or exhilarating parts of what was written. We revealed to ourselves and each other our vulnerabilities, what mattered to us. What was captured on the page was a living thing. Later, yes, of course, we edited the hell out of our small pieces. And in the editing, some of the pieces got longer and longer.

We’d hoped the 43 short fiction pieces would together show us a way to transition from oil to green energies. Propose solutions. But it turned out we were mostly bearing witness to the present moment, and that was enough. We were in the glass aquariums of the Zoom screens, isolated and spread across the country, and what we summoned were the sea monsters from the Mariana Trench of our subconsciouses: fears, hopes, loss, despair, kindness, love, empathy, and insight crawled out of the Petri-dish. Well, hello little guys doing your fancy dance.

This is what we caught a glimmer of: we had been gaslit, so many telling us everything would be all right. In fact, we had been telling ourselves we’d be all right. Of course, this isn’t an insight, but when it comes at you through vastly different stories, all sharp as cut diamonds, it has staying power. Each story a brief shock; it takes hold. So many of these stories are about losing a loved one to the climate crisis, in its various iterations.

Evan Davies writes a sci-fi story about a couple who are walking from a ‘warzone’ into wilderness. The man realizes his wife has left him in the first paragraph of this story: “She’d walked off in the gathering darkness, who knows where, anger and resignation in her posture. Would she come back, if he followed, if he could find her?” Davies is a Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering. His research focuses on numerical simulation of the impacts of alternative management policies on water resources at scales from local to global. His background informs the language of this brief story like a poem with a slant rhyme. Davies’s flash fiction piece is concise, as the prompt and timing of the exercise demanded, but one doesn’t get the feeling that Davies is sticking to the rules. The story is a gut-punch. His narrative appears simple, straight forward. The language is spare, unadorned. But the atmosphere of the story, the authenticity of voice, and the verisimilitude is unsettling and indelible. It will come back to haunt you, maybe when you are driving on an empty highway. When you are lost in thought.

The same can be said for these stories as a whole. They come back to a person. The power of certain images and lines, turns of phrase, dramatic turns in the plots. Bright flashes.

Take this opening line from one of Sourayan Mookerjea’s story, “Blot Spot of Neon Toxic”: “They didn’t find the body until they shot the blood-ulcered bear in the sludge pit.” The sibilance in ‘ulcered’ and sludge’ slips through the sentence like something befouled. Or becoming foul as the sentence unfolds. The images are sickening. Even the word ‘toxic’ in the title makes us stumble – should it be a noun rather than adjective? What is going on here? The the rhyme of ‘blot’ and ‘spot’ seems playful, as with childhood nursery rhymes. But this rhyme comes before the word ‘Neon,’ which can mean an intensity of colour or reflexivity or glow often used in signs warning of danger on worksites when used as an adjective, but also refers to the gas when used as a noun. The adjective followed by another adjective, and the absence of a noun suggests a kind of breakdown in the grammatical order of the title. The story follows with a terrifying breakdown of all things.

Janice Makokis’s story “No Speculation in Cree” weaves a tale of time travel, of ancestors and spirits able to manipulate quantum mechanics to communicate between the then and now and a time yet to come. The spirits tell the keepers of the ceremonies, that those who know the land, those who speak the language of the land and the ancestors, who have cultural knowledge and skills, and will survive. The robin will signal the real start of the hard times that are just around the corner, not using their song, but by their absence. When the robin comes back no more, their silence will be the knell that cannot be unrung. Janice’s story is her own take on a sacred Cree story, a prophesy, that will forever change how you feel when you see the flutter of a red-breasted robin. It’ll make your breath catch in your throat each season as relief washes over you and lifts the weight of worry that will now build every day between when the snow melts in early spring, and when you have your first sighting of the season. This story will leave you wondering if you, or your loved ones, will be among the few who survive to see new life emerge in a time after petroculture.

Sheena Wilson’s story “Alone and in Trouble” reveals itself as an immersive ghost story. Ghosts throughout the collection are metaphors for the ruins of industry, the lack of clean up, the saturation of toxicity in soil and water, and the decay of care, for the environment and each other. Ghosts are what haunt us following the destruction of nature. During this ubiquitous desecration, Wilson shows how women are handed the dirty end of the stick. Her prose is quick and transparent as glass. She captures the complex and critical moments of seismic cultural shifts that occur when the politics of energy transition provoke toxic masculinity, and the erosion of the social safety net, by nailing her characters on the page through gesture, dialogue, and action – however gentle or violent.

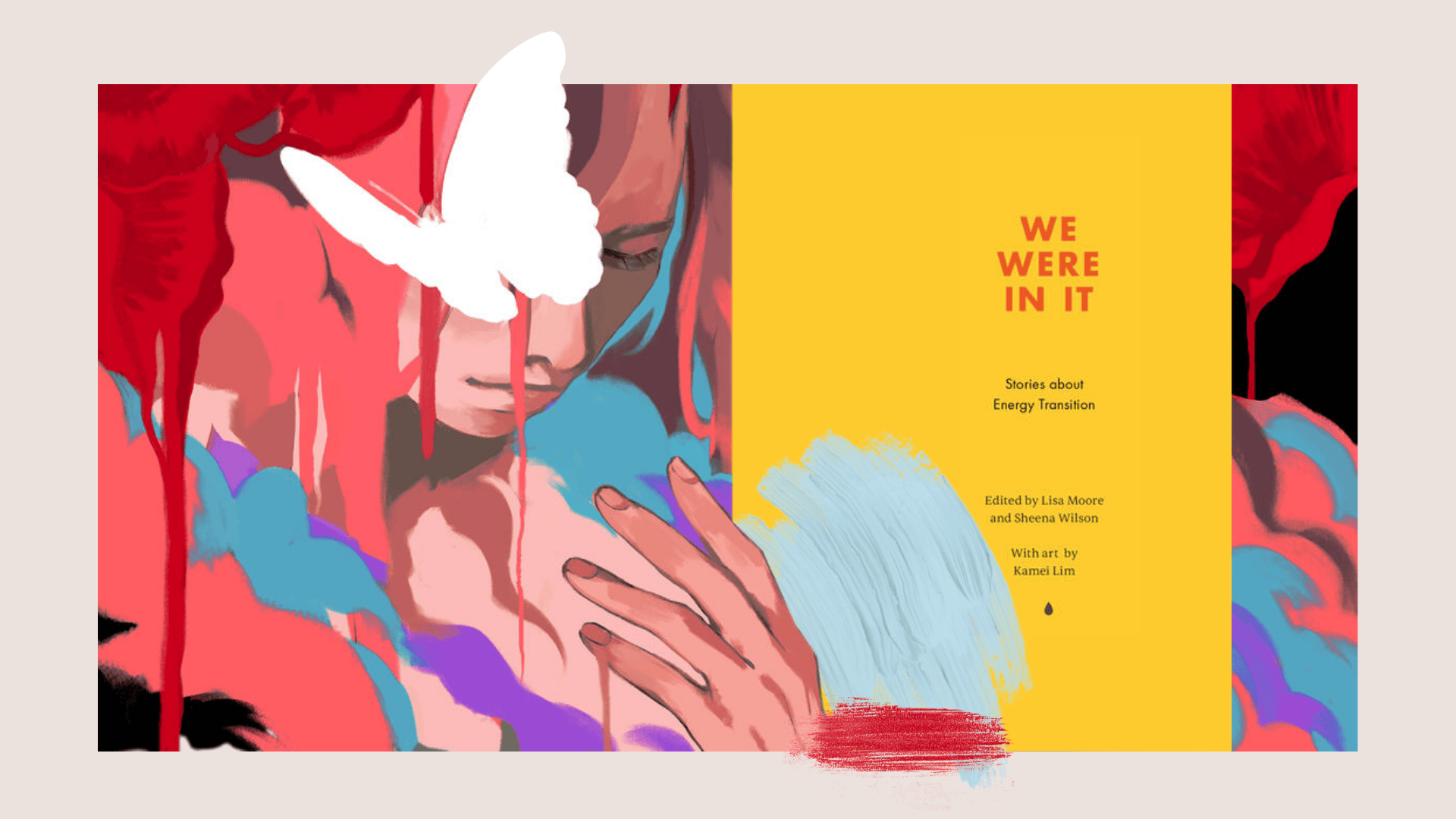

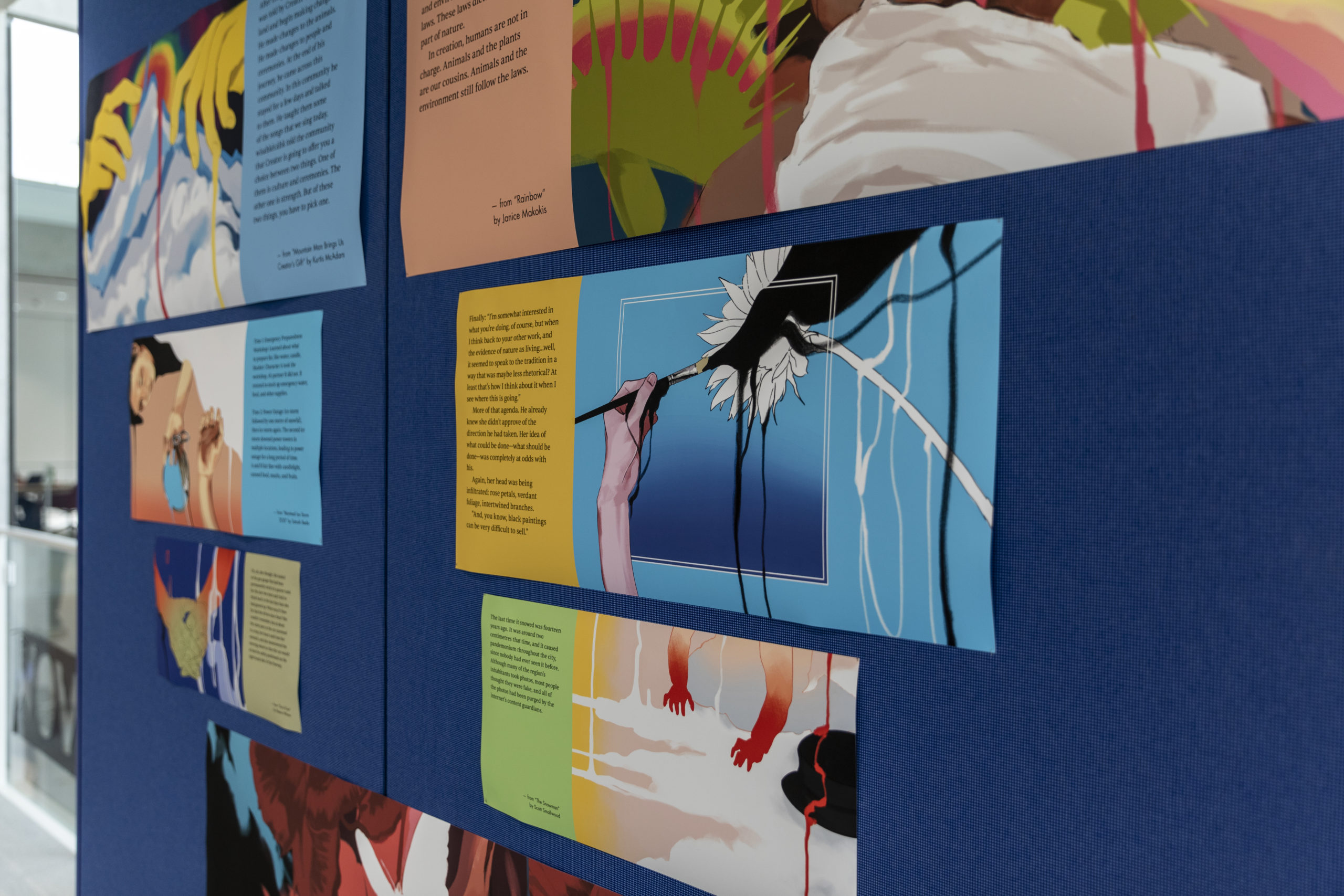

We have left until last the description of visual work that accompanies each story and is featured in the cover design because it was created quite near the end of the project. Rather than illustrating the work of all fifteen authors and their forty-three stories, artist Kamei Lim produces an impressionistic visual translation of the most piercing moments of each story. Her work completes each story in thoroughly unexpected and poetic ways. Perhaps Lim came the closest to the desire to approach the question of energy transition by offering solutions. The solution here is to remind us of the redemptive power of beauty; to remind us what we have to continuing fighting for. Seeing each image while reading the story it engages with makes the power of collaboration obvious, and how visual art is a language all its own. Lim’s images sing in harmony with the flash fiction of each writer, but the voice of the artwork is singular, individual and elegant in style, boldly colourful and somehow joyous. Often most of the subject is out of the frame and the synecdoche of hands suggests the whole figure, or the beak of a vulture connotes the carrion. There is a sense of regrowth in Lim’s images. Many of us are living in areas plagued by fires now, and these fires are predicted to be more virulent. Of course, bearing witness is always a healing act. But the notion of regrowth, in the shades of lime green, for instance, in shades that wake up the eye, bring to this collection the thing we hardly dare hope for: hope.

As Paolo Freire says, “Without a minimum of hope, we cannot start the struggle. But without the struggle, hope can become tragic despair.” The antidote is action. We want for you to read these stories. We want you to write your own stories, using the five writing prompts Moore has left for you to discover end of the book. Sharing stories is an important climate action.